Ann Marshall, director of research

Of the many good ideas that the Heard Museum Guild has had, establishing a museum shop and bookstore is among the best. When a June 1958 Arizona Republic newspaper article described the Guild’s plans for “a sales room,” it sounded very much like a basic museum store, selling “pamphlets, books, souvenirs, and reproductions of museum articles.”

Perhaps the reporter could be forgiven for a rather inaccurate description, since the article was written approximately six months prior to the shop’s opening on Saturday, Nov. 15, 1958. What was being planned was distinctly different from the average museum store, charting a course that has continued throughout 63 years. The chair of the Guild shop committee, Mary Ann Voorhees, was quoted in a November Phoenix Gazette article as saying, “We only want to stock the articles that we can safely say are the genuine, true representations of what can be seen in the museum. The emphasis at the museum is placed on Southwestern Indians and the largest part of our stock right now is the Navajo and Hopi jewelry, rugs, and pottery, as well as Apache, Pima basketry, and some beadwork.” The reproductions mentioned in the early article did exist in one respect, as Voorhees referenced an unnamed local artist who created reproductions of certain Mexican and Peruvian archaeological finds. The store was open every day except Monday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Sundays from 1 to 5 p.m. The museum was closed during the summer, from the end of May through September.

Funds to stock the store were granted by the museum’s board of trustees at there commendation of Lloyd Kiva New. New, chair of the board program committee, moved to allocate $2,000 to stock the “sales room” at the Sept. 18 meeting of the board, and the motion passed unanimously. An artist, fashion designer and educator, New was the first AmericanIndian member of the Heard Museum Board of Trustees. He had joined the board in 1952, and his designer fashion boutique in Scottsdale’s Craftsman Court made him keenly aware of a museum store’s potential. The approval was a huge vote of confidence in the Guild’s ability, given the very limited funds with which the museum operated. Those helping to gather the shop inventory included New and Tom Fitzwater, who was associated with Indian exhibits at the Arizona State Fair. Voorhees said, “We have premium articles from exhibitors at the [state] fair, and at the Gallup, N.M. Indian ceremonial. The silver work is from the Navajo Arts and Craft Guild in Window Rock.” She also mentioned help received from Hopi artist Fred Kabotie, who was actively involved with developing and presenting Hopi arts.

The “Gift Shop,” as it was called then, probably opened in one of the original small galleries to the left of the museum entrance. The year 1958 was a time of growth for the museum. The addition of the West Gallery gave the museum a gallery for changing exhibitions. (For reference, in today’s space, the West Gallery was located across from the Gallery of Indian Art, now the Jacobson Gallery, which had not yet been built.)

Success came quickly. In January of 1959, a net profit of $500 was noted, with profits in each successive month. By September 1960, the Heard’s member newsletter announced that the“gift shop has moved and expanded” into “a glamorous new setting.” The shop and its contents had been moved from the front room on the west side to the solarium leading to theWest Gallery, with new furnishings and decorations. Moreover, in 1961, profits from the shop, combined with earnings from the Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair, made it possible for the museum to be air-conditioned. The museum would no longer need to close for the entire summer.

Through all of this time, Voorhees had led the Guild’s shop committee, but in the October 1961 member newsletter it was announced that “Mrs. Ruth Dickenson, who previously has operated her own store in Scottsdale, is taking over management of the Gift Shop in the museum for the Guild.” Dickenson was a volunteer and was supported by eight Guild volunteer salespeople. Dickenson enjoyed international travel. In an unsourced July 1962 clipping in the museum archives headlined “South American Buying Trip,” Dickenson characterized her management and buying for the Heard Gift Shop as a “true labor of love.” At the time, she was sailing from Los Angeles by Norwegian freighter to Panama, where she would purchase Kuna molas (traditional handmade textiles), before flying on to Peru for further purchasing of folk crafts. A trip to Thailand brought temple bells and teak wood elephants to the museum. For a time, a diverse inventory of lower-priced items seemed to increase.

Growth and change came every year for the shop. By May 1962, the Guild was able to repay the $2,000 investment from the museum’s operating fund.

In 1963, the Guild board voted to change the name of the Gift Shop to the “Heard Museum Shop.” The shop expanded into the original museum galleries that today house hands-on activities and the Harnett Theater. Although books were not mentioned in the new name, books, maps and pamphlets were an important part of the shop’s inventory. In 1965, the museum published a brochure exclusively featuring the books available in the shop. From the beginning, support for the museum’s educational mission was key.

In January 1966, the Guild reported to the board that the shop was outgrowing part-time volunteer management and needed paid management. The urgency of that need was alleviated for short time, as in June 1968, the museum closed to accommodate construction of a major three-story expansion on its east side and on the west side a second changing gallery, now the Jacobson Gallery, designed by Arizona architect Bennie Gonzales. The expansion was precipitated by the 1964 gift by Senator Barry M. Goldwater of his katsina doll collection.

Following the museum’s March 31, 1969, reopening, Lovena Ohl was hired as the manager and buyer for the shop. Ohl’s extensive knowledge of American Indian art and artists launched the shop from what had been characterized as a souvenir shop into what Sunset magazine called one of the finest museum shops in the country. Ohl brought the focus back toNative artists of the Southwest and bought art with a wide range of price points, some many times higher than what had been purchased previously. But her extensive contacts with collectors and knowledge of leading artists meant that important sales took place. A 1974 newspaper article referenced Ohl as being at the “center of all the excitement generated by the current interest in Southwest Indian arts” and cited Ohl’s dedication based in a desire to help the museum, the artist and the buyer. She worked closely with the best artists, including Fred Kabotie and Charles Loloma. At the time of Ohl’s death in 1994, Loloma’s niece, jeweler Verma Nequatewa, said, “Lovena was the one who helped my uncle with his career. She put on a one-man show for him at the Heard Museum. She always said that ‘Charles was my best teacher.’” Ohl left the museum in 1977 to manage the Lovena Ohl Gallery in Scottsdale. In 1978, she established the Lovena Ohl Foundation, and contributions from the Foundation to the Heard are recognized in the gallery named for her.

During Ohl’s nine-year tenure, the museum shop expanded to include all the original galleries along the museum’s west side, including a space dedicated to books and notecards. In Ohl’s first year, profits from the shop rose from an estimated $10,000 to $22,000. The Guild yield edits meeting room to become a workroom and office for Ohl where she could meet with important, and sometimes celebrity, collectors. In February 1974, the Guild transferred responsibility for the shop to the museum and the museum director. The Guild would continue in an advisory capacity, and monies were to be processed by the Guild. Guild members continued to serve as the sales staff for the shop and bookstore.

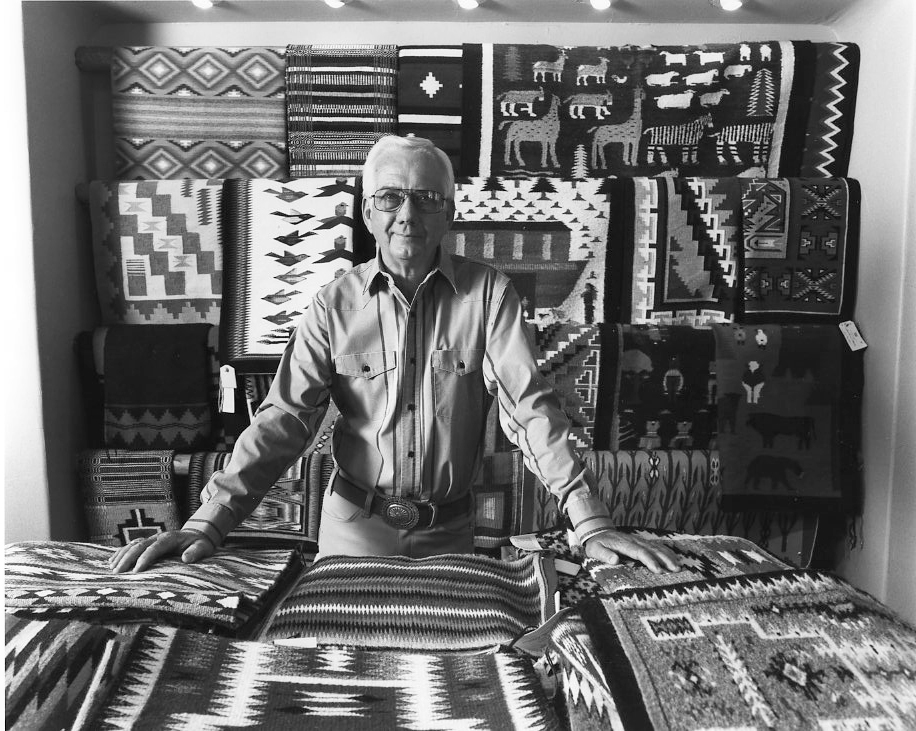

Following Ohl’s departure in 1977 to establish her Scottsdale gallery, Byron Hunter Jr. was hired to manage the shop. Coming from a family of traders, Hunter had managed trading posts on the Navajo Nation and at First Mesa on the Hopi reservation before opening Hunter’s Trading Post on Camelback Road in Phoenix in 1970. With lifelong connections to many artists, Hunter was uniquely qualified to lead the shop into the 1980s. Hunter remarked to Arizona Republic writer Linda Helser that “Several of the families I trade with now, my father traded with back in the ’40s, and this becomes a place to display their things.” His extensive experience working with Hopi katsina doll carvers made it possible to greatly expand offerings of the figures. He also widened the price range of art to make the shop inventory affordable to more museum visitors and beginning collectors. Hunter was buying and managing the shop during a period of considerable change, as collectors from Europe and Asia became interested in American Indian arts. He told Helser that the museum was seeing more German, English and Japanese visitors who were new collectors, and he stressed the importance of the education that the shop offered these collectors, along with a deserved reputation for authenticity. The education was badly needed, as fraudulent dealers and traffic in fakes grew with the popularity of American Indian art forms.

When the museum expanded in 1983-84, the shop was relocated to the southeast corner of the museum with a separate entrance for those not visiting the museum. Under Hunter’s leadership the shop experienced several firsts: its first members-only sale in 1985, and in 1989 its first printed catalogue. In 1994, the name of the shop formally became “The Heard Museum Shop and Bookstore.” The expanded space had offered the opportunity to present more publications and recorded music.

In the fall of 1997, after 20 years leading the Shop and Bookstore, Hunter retired. Bruce McGee was hired in 1998 as the new manager. McGee had a background very similar to that of Hunter, including experience with family trading posts. He had grown up at Hopi, where his father had owned the Keams Canyon Trading Post for nearly 61 years. As a third-generation arts trader, McGee began his career in 1967 at his family’s post in Piñon, Arizona. At the Heard, McGee continued the tradition of working with artists who were longtime friends. Noting McGee’s knowledge, Heard Museum Director Martin Sullivan remarked in 1999 that “McGee is able to recognize the masters and those in the making.

During McGee’s tenure, which continues today as director of retail sales, many changes have taken place that provided opportunities to better present the full range of American Indian art. With the museum expansion in 1999, the shop moved into its present location, with Books & More across the central courtyard. By 2001, the shop had an online presence. A further expansion in the summer of 2006 added 2,400 square feet of space to create the Berlin Gallery, recognizing longtime Heard supporters Howard and Joy Berlin. The gallery was created to focus attention on fine arts by recognized and developing artists. Writing about the Berlin Gallery, Heard Museum Director Frank H. Goodyear Jr. noted that of the 17 artists represented in the Gallery, 15 were in the museum’s permanent collection. Goodyear’s comment highlighted along-standing fact and unique feature of the Shop, that the quality of art in the Shop was such that, over the years, major pieces from the Shop had been acquired for the museum collection—a circumstance that definitely does not occur in the standard museum shop.

A further revision to the mission of the gallery in 2015 created the Collector’s Room with the full range of arts presented and the entire sales operation renamed the Howard R. and Joy M. Berlin Shop and Bookstore. Today, a knowledgeable staff joins McGee in running every aspect of the shop, welcoming and encouraging artists, and educating visitors and collectors. After 63 years, Heard Museum Guild volunteers remain an important part of the shop, offering a welcoming presence and informed advice to visitors. Made possible by countless hours of volunteer service, the shop remains one of the very best ideas the Guild ever had.