Ann Marshall, director of research

It takes courage to start a museum, but it takes a great deal more to continue when your husband of 36 years dies just as the exhibits are being installed. Maie Bartlett Heard had that courage in abundance and saw the Heard Museum through its first 22 years. Her civic activities are well documented in the many awards she received in her later years prior to her death on March 14, 1951—22 years to the day after Dwight Heard’s passing.

Histories of the museum’s founding invariably and appropriately begin with Dwight and Maie Heard’s international travels. Their collecting started prior to their marriage on August 10, 1893, in the Chicago home of Maie’s Father, Adolphus Bartlett. The couple traveled as far as Egypt in a family party, and their findings would mark the beginning of what would eventually become the Heard Museum.

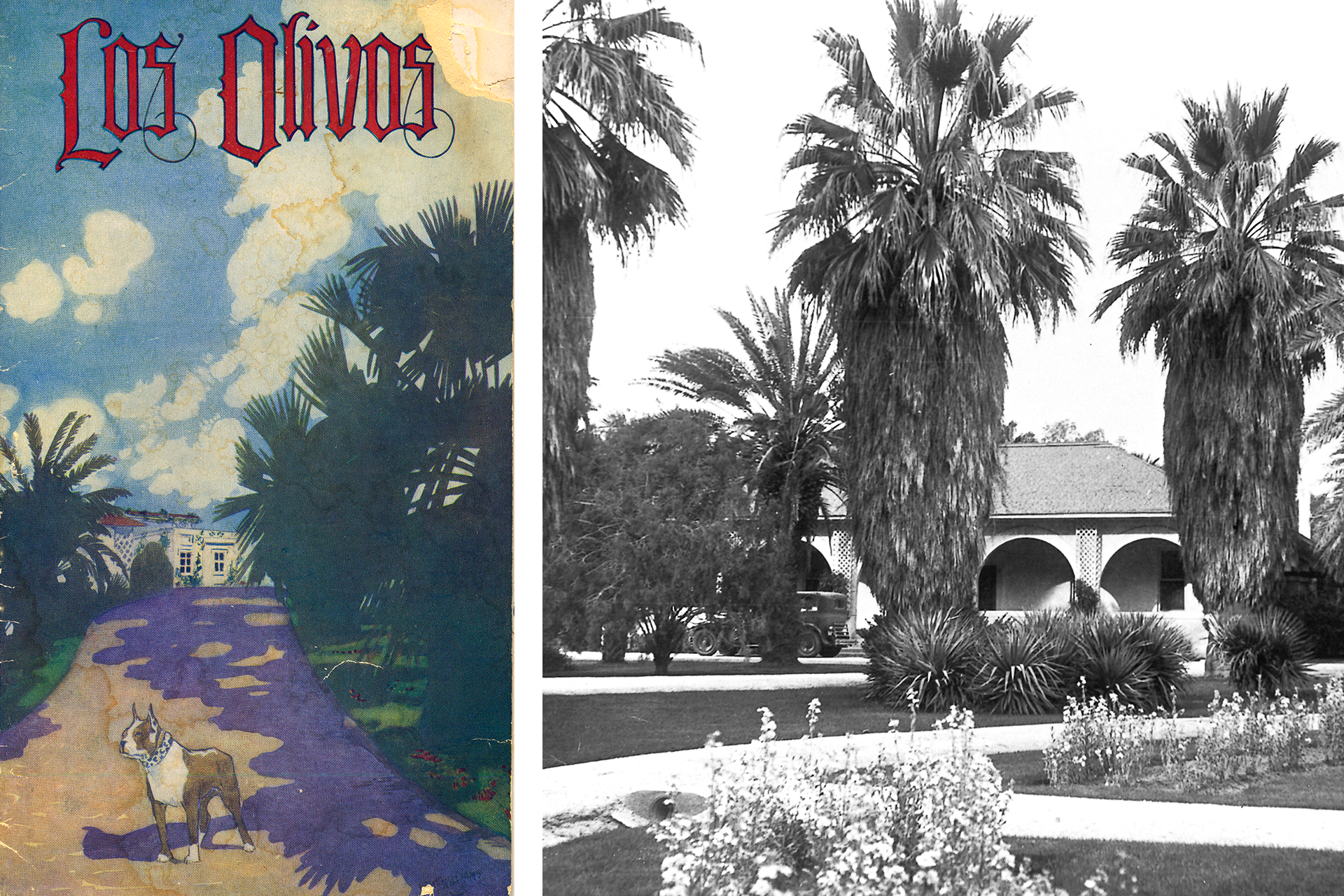

Plans for continuing married life in Chicago changed in 1894. Dwight developed respiratory problems and needed to seek a more healthful climate. The couple spent 1894 traveling through Texas and New Mexico by horse and buggy. An 1895 a train trip with Maie’s father took them to Phoenix, where a planned stop of 24 hours led to a two-week stay. Just four months later, the Heards purchased their first property, which they named Buena Ranche, located at what is now 51st Avenue and McDowell.

The Heards made a good team. Mr. Heard, a big man, was characterized as outgoing and energetic. The list of enterprises he was involved with is long and includes real estate developer, ranch owner, newspaper publisher, political party participant and candidate for governor of Arizona. Through his father-in-law, Dwight Heard was an important conduit for Chicago investment funds in capital-poor Phoenix.

occasions including a 1916 stay as a houseguest at the Heards’ home, Casa Blanca.

Much has been recorded about Dwight Heard; much less about Maie Heard. In contrast to her husband, Mrs. Heard was described by her longtime secretary and friend, Eula Parker Murphy, as being “quiet, tiny and fragile-looking.” A 1964 newspaper article written by George F. Miller as Scout Executive of the Theodore Roosevelt Council, and a personal acquaintance, referred to her as “a slight, frail giant” and “a tower of strength … a courageous person [who] often stood almost alone to fight for the rights of individuals.” A neighbor and friend Barbara Williams, who would later become the president of the Heard Museum’s Board of Trustees, echoed Miller’s assessment of Maie as “pleasing and gentle of manner, which hid a will of iron.”

The years between 1895 and the early 1920s saw the Heards traveling back to Egypt and the Sudan, to Mexico, to Hawaii, to Pacific Expositions, to Yosemite, and throughout Arizona. Their second home, Casa Blanca, became filled with mementos of their travels, even to the point of having to store some pieces.Winifred Heard, wife of the Heards’ only son Bartlett, recalled the circumstances around the Heards’ decision to start a museum in an oral history recorded by the University of California, Berkeley’s Bancroft Library: “When I came into the family in ’21, the house was just so crammed full of things that Mrs. Heard and I were talking one day about what to do with them, and she was saying that she would sort of like to build a small building to put them in. I said ‘Why don’t you?’ She felt that this was a little presumptuous, but I urged heron; and so that’s how the Heard Museum started and why it was on the grounds [of the Heards’ home].”

It is important to note that what the Heards planned was entirely different from anything existing in Phoenix at the time. The Arizona Museum was focused on Arizona history. In 1924, the City had been given the land on the site of a Hohokam mound, and where the Pueblo Grande Museum would open in 1929. The museum the Heards envisioned would have an international scope and a focus on indigenous people.

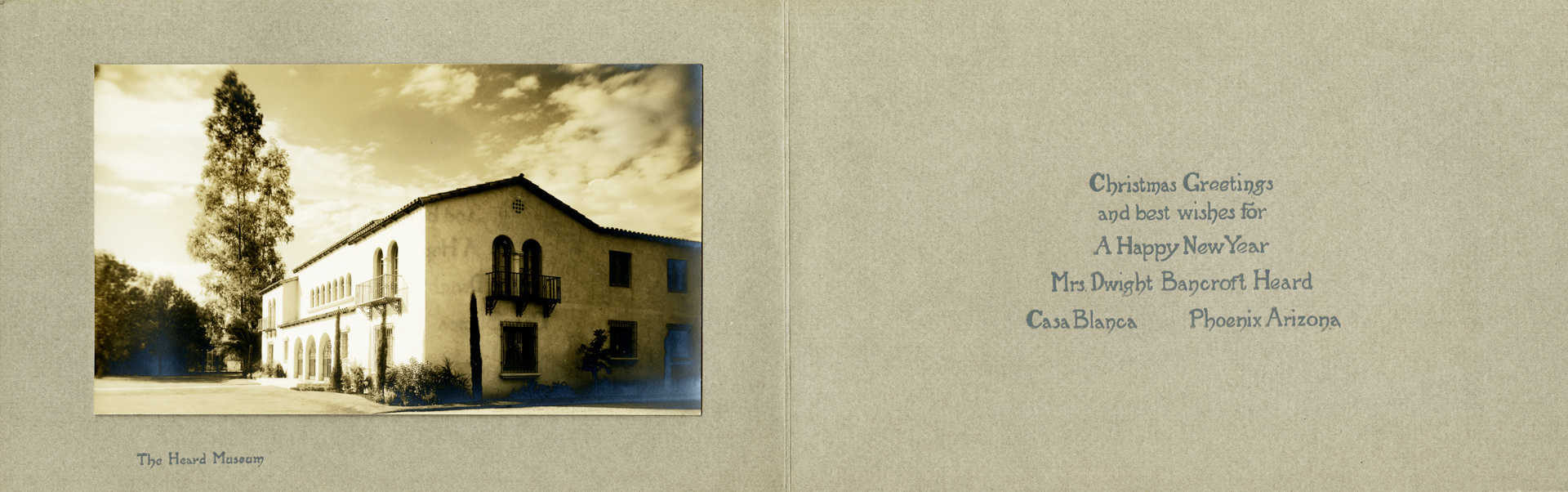

Planning for a museum became more specific when in 1925 Dwight provided in his will $75,000 to be used by Maie “for construction, maintenance, and endowment for any form of benefaction for the benefit of Phoenix and vicinity.

Augmenting the collection was a next step. By at least 1927, Herb BraMé and Allie WallingBraMé of the Arizona Curio Company (Allie would become the museum’s first curator) were working on commission purchasing indigenous art from people of the western United States.

Chicago architect H. H. Green was then hired to design the museum. With the Heards actively involved, Green created a structure that fit into the residential nature of its surroundings. Eula Parker Murphy described the planning of the museum, “They really had fun on this one. They sent for books on Spanish architecture, they pored over books about museum display cases, they designed some of the furniture and drew the plans for the wonderful wrought iron gates, and they saw it all built just as they dreamed.”

The building was completed in 1928 and cost in total $42,000. The museum had eleven galleries between the two floors, an auditorium, a kitchen, a library, an office, an apartment for a caretaker, and no collections storage. Installation of the galleries proceeded shortly after completion. According to Winifred Heard, it was exertion from handling Navajo textiles during a meeting at the museum with the Wetherills (probably John and Louisa) to discuss the textile installation that led to Dwight’s fatal heart attack later that day.

The articles of incorporation and formal announcement of the founding of the Heard Museum followed the settling of the estate on June 18, 1929. The very next day, the first meeting of the Heard Museum’s Board of Trustees took place. Only two people were present—Maie as President and her son Bartlett as Secretary/Treasurer. Maie’s sister Florence Dibell Bartlett was also appointed Vice President, but as a resident of Chicago, was not in attendance. At that first meeting it was decided that “as near as practicable the board would have an equal number of men and women, not less than three members or more than 25 with a majority Phoenix residents.”

The second meeting of the Heard’s board—again, just Maie and Bartlett—included the decision to send out letters inviting “representative citizens of Phoenix” to join the board. The museum’s strong emphasis on education was apparent with the establishment as a permanent policy off our ex-officio members to include “the principal of the Phoenix high school, the superintendent of the city school, the superintendent of the county schools and the president of the Phoenix Parent Teacher association.” Unfortunately, the other Phoenix school, the Phoenix Indian School, was not included.

There was no acquisition fund. Mrs. Heard simply bought what she thought the museum

needed. She bought from local Indian art stores and was actively purchasing from the Fred Harvey Company. Maie was immersed in every detail, no matter how small.

When the Heard Museum opened on December 26, 1929, it was a low-key public announcement in the Arizona Republican. Less than one column inch, the announcement consisted of a headline “Heard Museum to Open” and one sentence—“Beginning December 26, the Heard Museum, 22 East Monte Vista Road, will open to the public every day except Sunday, from 10 to 4.”

Shortly following the opening, standing committees were created that established policy for decades to come. The House Committee established the policy that the auditorium would not be available for purely social affairs—the meeting had to have some interest or theme relating them to the museum’s mission. Successes in attracting club meetings in the first year of the museum led to establishment of fees and essentially began the private use revenue stream—decades before the 1980s, when the museum initiated its current program.

The Program and Publicity Committee, chaired by Winifred Heard, was the most active in their charge to encourage schools, societies and other appropriate organizations to visit. At the committee’s first meeting, many programs for children were outlined including Saturday morning story hour, traveling exhibits with a storyteller sent to schools, handcraft classes, and even the possibility of cooperation with playgrounds for over the summer. For adults, the committee planned outreach to clubs encouraging them to hold regular meetings at the museum, a speakers bureau, and lectures related to exhibits. Ambitious, breath-taking and perhaps naïve are three words that come to mind in reading the list. This was a museum without an educator or volunteer guild.

There were definite early programming successes, including a meeting of art teachers from all over the Valley and ten meetings of women’s clubs booked through the next year, all before the museum closed in May (and re-opened in October). In the early 1930s, Miss Samuels was brought in as the museum’s Storyteller, and Mrs. Margaret Hyde as an outreach speaker for schools. Unfortunately, the museum could not maintain the extension program, as the Great Depression took a deeper hold on the nation’s economy. It is very important to note that 90 years later, the museum has continued to develop and present these same original programs.

Adult programs in the form of lecture series were also vitally important. The first speaker (whose name is not recorded) was an initial misfire, as the individual had never visited the museum and assumed it was a history museum. Subsequent speakers in following years included Charles Avery Amsden, at the time the Secretary/Treasurer of the Southwest Museum in Pasadena, who spoke on Navajo textiles. Dean Byron Cummings of the Arizona State Museum, Kenneth Chapman of the Laboratory of Anthropology in Santa Fe, Mrs. Heard’s sister Florence Dibell Bartlett, a folk art collector and the founder of the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, spoke on “Colorful Guatemala,” and Harold and Mary-Russell Ferrell Colton, founders of the Museum of Northern Arizona, spoke in1934 on the Hopi Craftsman Exhibition. One of the most popular speakers was Barry Goldwater, before his senatorial days, who showed films about going down the Colorado River which had to be shown on two successive nights to accommodate audiences.

Through the years, it was Mrs. Heard who was mainly responsible for communicating with speakers and transmitting content to the newspapers, the Arizona Republic and Phoenix Gazette, with whom the museum maintained a close relationship. One example from 1950 is a typewritten article announcing Dr. George Brainerd’s talk. Eleven paragraphs later she summarized, “This is an awful mess—just bits picked from several books on the Yucatan—mostly from National Geographic. I could find very little that seemed appropriate for publicity, and am not sure that you can use any of the above. It is after midnight and the books are over at the Museum or I would try again.”

Maie was involved in acquisitions as well. She responded personally to potential donors with unfailing grace. In one letter she explained that “As you probably know, our small museum is already crowded and we can find space for only those articles which are lacking in our collection or are better than anything we already have, in which case we remove the inferior items.”

There was also no need for an acquisition fund. Mrs. Heard simply bought what she thought the museum needed, including purchases from local Indian arts stores and from the Fred Harvey Company. Of course many dealers approached Mrs. Heard about purchases. One exchange of letters in April of 1930 was with Fred Wetzler of Wetzler Supply, Furniture and Hardware in Holbrook, Arizona. Wetzler was on his way to the coast with a collection of Navajo rugs and would be passing through Phoenix on Sunday morning. He offered to bring them to her residence, but Mrs. Heard told him to go to the museum and meet Mrs. BraMé, who “will inspect them and let me know if it will be worthwhile for me to run over.” A handwritten note on the letter from Mrs. Heard indicates that she bought from this group a textile for $200, originally priced at $1,580.

One colorful exchange of correspondence took place in 1929 between Mrs. Heard and artist Lon Megargee, who wanted to sell Mrs. Heard some Spanish antiques acquired on a painting trip to Spain. Mrs. Heard’s response questioned one of the chests saying, “My attention has been called several times to the fact that the carved panels appear to be modern work. On the continent they are so clever in the matter of these reproductions that I presume you did not consider the possibility that the chest had been ‘improved’ for the trade.” To which Megargee fired back, “My Dear Mrs. Heard—The bold statements of the individual or individuals who suggested that the carvings on the chest was of a later period than other parts brands himself as an ignoramus of the first water—no one who had real knowledge relating to Spanish antiques could come honestly to such conclusions.”

Today, looking back over 90 years, several things are striking about the early years of the Heard Museum. At the time of the Heard’s founding, many museums were defining themselves as research institutions and conducting field work. Some museums attempted to do both. The Heard Museum has always had a commitment to presenting to a general audience information about indigenous people through exhibitions, programs and publications. Also, its exhibitions and collections have always included the art of living artists and contemporary works. Its broad, international scope has changed over the years as other institutions and other sources of information emerged, offering the Heard the chance to dive a bit deeper into regional subject matter. Perhaps the thing that is most striking is the courage and devotion displayed by Maie Bartlett Heard over the first 22 years of the museum’s existence that began everything we are today.