Reflecting on Toward the Morning Sun: Navajo Pictorial Textiles from the Jean-Paul and Rebecca Valette Collection

Roshii Montano: I think you come from an interesting perspective because you’ve spent so much time with the collection. Have your feelings surrounding this project changed in any way?

Ninabah Winton: When we first started working with this collection, I was hesitant. My family taught me that you shouldn’t discuss the Nightway out of season, and you should never weave the Ye’ii Bicheii dancers. My perspective on that changed a little bit through the textile review workshops, when we were able to look at them as art objects, as opposed to ceremonial pictorial weavings. We were trying to understand the textiles’ construction. In previous workshops, the information has been limited because we intended to seek out the pictorial subject. This year, I think it was focused on appreciating them as they are.

RM: I felt similar. Going into this project, I didn’t know how we should be talking about these textiles—what was and wasn’t okay. I did appreciate the textile workshops, because everyone came in with different perspectives. They were all willing to speak on various aspects of the textiles. For example, Venancio Aragon was so excited to talk about the colors, dyes and production.

NW: It was so nice to be together in that space with the weavers we invited to see the collection. It felt very Navajo.

RM: Yes! Being together, laughing, talking about our personal experiences, our grandmas, the people in our lives who are weavers—it was beautiful to have that social connectivity. Sometimes in our discussions, we were so overtaken by a textile—either from beauty or because we were conflicted. There were silences, but we were connected in this silence.

NW: I just thought of my favorite moment. It was when Raven Chacon teased me by shushing me (laughs). It was significant to have someone who wasn’t a weaver, a dancer, who is more in sound art and that contemporary new-media sphere. It was fascinating to hear his perspectives.

RM: The curatorial team talks to each other every day about the exhibition content, cycling through similar thoughts. With the textile workshop, we get to hear about the things that standout to them. Velma (Assistant Curator Velma Kee Craig) summarized this idea well; she talked about each workshop getting more refined in the details being brought out. In our last workshop, Kevin Aspaas and Tyrrell Tapaha spoke about the prominence of the colors red and orange in the collection, and I just thought, “Yes, of course!”

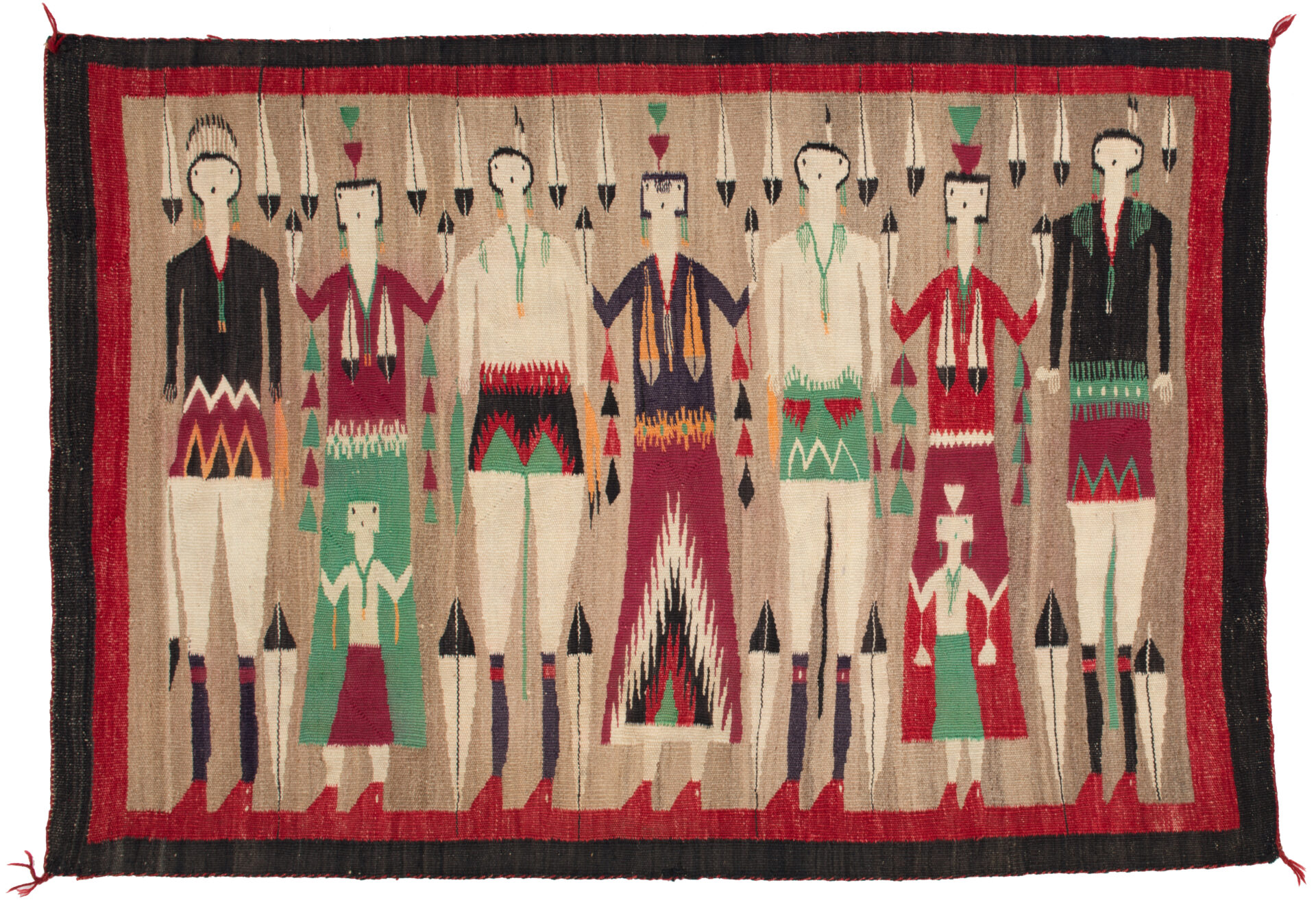

Artist Once Known (Diné), Ye’ii Bicheii Pictorial textile, 1920s. Four-ply commercial wool yarn, cotton warp, aniline dyes, 60 3/4 x 32 1/4 inches. The Valette Collection at the Heard Museum, Gift of Jean – Paul and Rebecca Valette, 4930-48

NW: It’s always a different experience when you view the collection with fresh eyes. I was excited to hear Tyrrell’s perspective, because he’s the grandson of master weaver Roy Kady. It was so cool to listen to Kevin and Tyrrell talk about the technical aspects of weaving, like warp to weft ratio, and a Navajo-defined standard of quality, imposing those Navajo standards, as opposed to institutional ones.

Something that stood out to me was the diversity of the participants in each workshop. We’ve had people in their 60s and 20s look at the collection. This last one was all male weavers, when in the past it had been all female. It’s always assumed that only women are weavers, and I try to neutralize the language I use when talking about weavers, using terms like “they/them” in my practice.

There’s also been discussion in these workshops about “Well, the weaver wouldn’t have woven it if it was truly sacred.” It’s like, “Do you know what they were up against?” During the Great Depression, one trader offered weavers $150 per snake design, weaving pound rugs, and then all of their sheep get slaughtered … It was a complicated socio-economic dynamic.1

Sometimes in our discussions, we were so overtaken by a textile — either from beauty or

because we were conflicted. There were silences, but we were connected in this silence.

RM: The Valettes wanted the collection to be here at the Heard, closer to Diné people. What do you think needs to be done further in terms of research and care?

NW: I would like to see more invitations for interpretation, rather than people seeking it out or expecting Diné to know the museum holds this collection. I would like to see interdisciplinary collaborations. There’s fertile ground for new collaborations. There was this concept of synecdoche I was reading about, and how weavers don’t just put sheep’s wool into the textile. There are portions of their body, their hair, and the oils from their skin. Traditionally, those things—if you allow them to get away from you, they can bring harm.If we aren’t taking care of this collection with all of its power and its personhood effects, I wonder if we are inviting or perpetuating harm. I would love to see them receive additional conservation care.

RM: One thing that we wanted to emphasize is the theme of healing. Have you learned anything about healing as you’ve been spending time with the collection for three years?

NW: It’s been an interesting year because of the pandemic. Coming to the subject of healing after a period of intense trauma makes me try to empathetically understand or situate where these weavings are in history. In my way of seeing, some pieces are woven with healing in mind. There are gestures of protection woven. In my research and writing, I’ve been intentional in understanding the traumas that inform why. When it comes to energy and healing, these textiles have life or personhood. It’s an embodied practice to handle and care for them.

RM: I like what you say about your experience going through the pandemic with this collection in mind. It brought an interesting element to my understanding of healing. We talk about weaving as a practice of healing. I’m thinking about the beginning of my weaving practice and how I situate healing in my body, through the loom, and into a textile. With this collection, in particular, I have felt the need to be very careful and respectful. We’re Navajo, and we have an indefinable reverence for these textiles. They are living.

NW: My mom once defined life force, and she said even your car has life force. That’s why you have to take care of it; that’s why you put bitter herb on it (laughs). In the beginning, it was hard to let go of the reservations I had about the collection because it was so strong to me. Having those stories, having that living memory, and understanding [that] you just don’t do it.But having that memory allowed me to make choices towards that praxis of care andIndigenous knowledge.

RM: It’s challenging to conceal certain aspects of our sacred knowledge while trying to convey the narrative for the exhibition. However, we want to bring points of memory to the forefront for the people that this collection is for, right? I do value the time that I’ve spent with the textiles, and it’s made me think more deeply about a lot of the things that we’ve brought up in this conversation. This experience has further contributed to my understanding of collective care, healing, and understanding of a textile’s personhood.

[footnote]

- Peake, Nancy. “Chapter 1: Through Navajo Eyes: Pictorial Weavings from Spider Woman’s Loom” ed. Tad Tuleja. Usable Pasts: Traditions and Group Expressions in North America. University Press of Colorado: Utah State University Press. 1997. In March 1989, Nancy Peake interviewed Walter Kennedy, who ran a trading post in Dennehotso, Arizona from 1950-1982. Kennedy allegedly stated: “Navajos have a thing against snakes, and some even say a woman went blind after weaving a yei rug with snakes,” According to Peake, Kennedy nevertheless offered to pay his weavers $150 for each snake woven into a rug. ↩︎