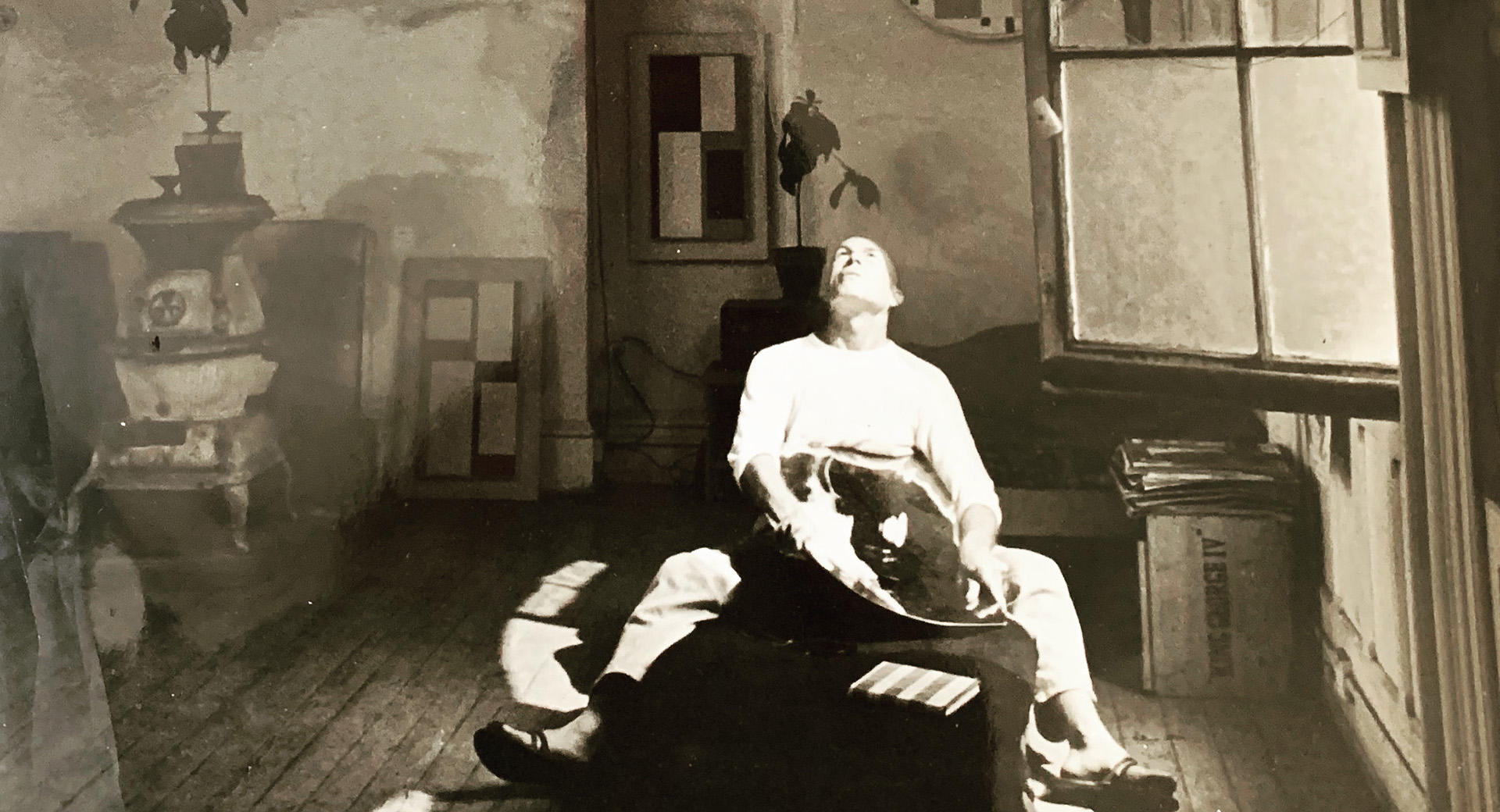

Joe Baker, co-curator

Most of the art world understands Leon Polk Smith in terms of American Modernism. Smith is often compared to Ellsworth Kelly for his hard-edge painting or the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian for his abstraction. However, little attention has been paid to the significance and influence of Smith’s Oklahoma upbringing.

Smith was born near the town of Chickasha in Indian Territory in 1906, just before Oklahoma statehood. The second of nine children, he grew up on the ranches and farms of rural Oklahoma. “Leon grew up with the Chickasaws and Choctaws and understood the Indians’ philosophy. He felt the abstraction in their celebration of dance and song. His special relationship to nature possibly arose from growing up on a farm and ranch,” said Robert Jamieson, Smith’s assistant and longtime companion, in an interview for a 2001 book. Theancient Kiamichi Mountains to the east and the tall grass prairie to the west and north provided the stage for Smith’s imagination. The surrounding Native communities provided the rhythm of what would become his visual abstractions.

After graduating from Pocasset High School, Smith attended Oklahoma State College (East Central State University) in Ada, graduating in 1934 with a bachelor’s degree in English and a teacher’s certificate. Smith arrived in New York in 1937 to attend Columbia University Teacher’s College and earned a master’s in educational psychology in 1938. It was while attending Columbia University that Smith first saw the work of Piet Mondrian, Constantin Brancusi and Hans Arp. He also met the choreographer and dancer Martha Graham, whose influence and friendship remained true throughout his lifetime. After traveling to Europe and Mexico and teaching in several different locales, he moved to New York City in 1944 to commit full-time to making art.

Leon grew up with the Chickasaws and Choctaws and understood the Indians’ philosophy. He felt the abstraction in their celebration of dance and song. His special relationship to nature possibly arose from growing up on a farm and ranch.

Unidentified artist (Comanche), shield and cover, c. 1880. Hide, cloth, colorpigments, eagle feathers, horsehair, 18 inches diameter x 42 1/2 inches long. Fred Harvey FineArt Collection, Heard Museum, 258CI-a.

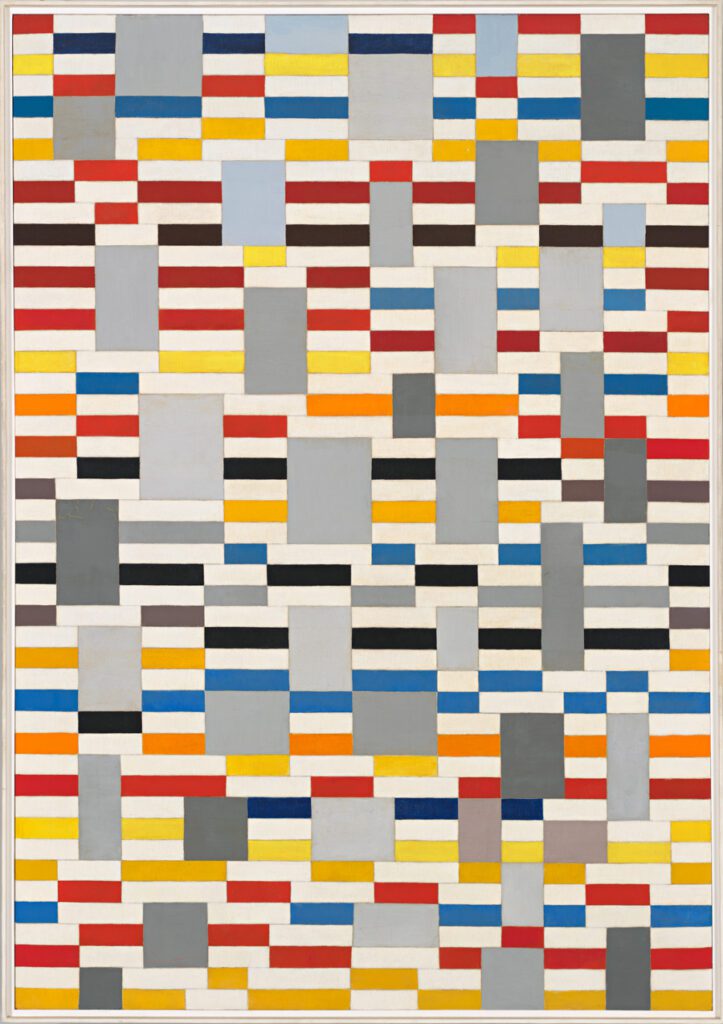

Having spent the first third of his life in Oklahoma, and now living and working in the creative community of New York City, Smith never leaves the landscape of the Southwest or the Native communities he knew there. It is from this unique cross-cultural vantage that Smith is able to read Mondrian’s geometric style as “an extension of the baskets and blankets he knew in theSouthwest,” says Randolph Lewis, professor of American studies at the University of Texas, Austin.

“In the Indians’ philosophy, thinking, and way of telling stories, much detail was left out, so much was abstract,” Smith once said. From the 1940s on, the landscape and Native cultures he knew resonated in Smith’s work. We see this expressed in the “Conversations” and “Constellation” series that define the artist’s mature work.

In the Indians’ philosophy, thinking, and way of telling stories, much detail was left out, so much was abstract.

Leon Polk Smith

Leon Polk Smith (American, 1906-1996), N.Y. City, 1945, oil and pencil on linen,46 3/4 x 32 3/4 inches. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Purchased with fundsfrom the Edward R. Downe, Jr. Purchase Fund and the National Endowment for the Arts inhonor of the museum’s50th anniversary, 79.24.

Leon Polk Smith: Hiding in Plain Sight, organized by the Heard Museum 25 years after Smith’s major exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, seeks to broaden our understanding of Smith’s work through a Native context. The Territorial Works display, adjacent to the main exhibition gallery, provides the viewer with cultural arts collected from Indian Territory—bandolier bags, cradleboards, pipe bags, shield and cover, ribbonwork—that provide design references to Smith’s work. Their abstract patterns and color combinations echo the forms and color-blocking often encountered in Smith’s work. It requires no great stretch of the imagination to discover what, all this time, has been hiding in plain sight.